As I plod away at reading some of the influential 16th- to 19th-century books in the life of the American evangelist James Brainerd Taylor (1801-1829), the latest one was Essays To Do Good: addressed to all Christians, whether in public or private capacities (abridged title).

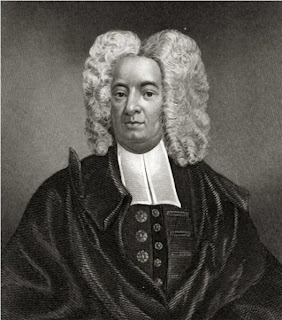

It was written by the prominent New England Puritan, Cotton Mather (1663-1728).

Among the 17 editions that appeared between 1800 and 1840, the 1816 "new and improved" London edition by editor George Burder is available online and for free at Google Books. It is a manageable and spiritually challenging 172 pages. (Burder's 1826 edition is also available at Google Books.)

Written in 1710, Essays To Do Good was popular among American and British Christians up to the mid-1800's. Harvard historian Perry Miller (1905-1963) considered it one of the most important books of the early eighteenth century.

The work even had a shaping influence on the non-Christian (Deist) Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). The famed American diplomat-statesman-scientist read the work when eleven years old. At sixteen, he borrowed from the book's theme when he pretended to be a middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood. The fourteen satirical letters from his pseudonym Silence Dogood were published in the New England Courant from April to October 1722.

The work even had a shaping influence on the non-Christian (Deist) Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). The famed American diplomat-statesman-scientist read the work when eleven years old. At sixteen, he borrowed from the book's theme when he pretended to be a middle-aged widow named Silence Dogood. The fourteen satirical letters from his pseudonym Silence Dogood were published in the New England Courant from April to October 1722.

Here are some quotes from Essays To Do Good. All page numbers are from the 1816 edited edition by Burder.

+ A power and an opportunity to do good, not only gives a right to the doing of it, but makes the doing of it a duty. (pp. vi, 4)

+ The firstborn of all devices to do good is in being born again [John 3:3,7; 1 Peter 1:23]. (p. 22)

+ Without abridging yourselves of your occasional thoughts on the question, 'What good may I do today?', fix a time, now and then, for more deliberate thoughts upon it. Cannot you find time (say, once a week and how suitably on the Lord's Day/Sunday) to take this question into consideration, 'What is there that I may do for the service of the glorious Lord, and for the welfare of those for whom I ought to be concerned?' (p. 35)

+ Those who devote themselves to good devices [works], and who duly observe their opportunities to do good, usually find a wonderful increase of their opportunities. The gracious providence of God affords this recompense to his diligent servants, that he will multiply their opportunities of being serviceable. (p. 36)

+ What I aim at is this: Let us try to do good with as much application of mind as wicked men employ in doing evil. When 'wickedness proceeds from the wicked [1 Samuel 24:13], it is done with both hands and greedily.' Why then may not we proceed in our useful engagements 'with both hands,' and 'greedily' watching for opportunities. . . . 'If you will not learn of good men, for shame, learn of the devil; he is never idle' (Hugh Latimer). (p. 27)

+ A workless faith is a worthless faith. (p.31)

+ Let no man pretend to the name of a Christian who does not approve the proposal of a perpetual endeavor to do good in the world. What pretension can such a man have to be a follower of the Good One? (p. 18)

+ Protestants, will you be out-done by Popish idolaters? O the vast pains which those [Roman Catholic] bigots have taken to carry on the Romish merchandise and idolatry! (p. 155)

+ 'Our rejoicing is this, the testimony of our conscience.' . . . 'A good action is its own reward.' Indeed, the pleasure that is experienced in the performance of good actions is inexpressible, is unparalleled, is angelical; it is a most refined pleasure, more to be envied than any sensual gratification. Pleasure was long since defined, 'The result of some excellent action.' This pleasure is a sort of holy luxury. Most pitiable are they who will continue strangers to it! (p. 170)

With an emphasis on self-denial, "Up and be doing" as a life maxim, and Galatians 6:10 as an oft-repeated Bible verse in James Brainerd Taylor's journal and letters, it is easy to see the impact that Essays To Do Good had on the "uncommon" Christian.

With an emphasis on self-denial, "Up and be doing" as a life maxim, and Galatians 6:10 as an oft-repeated Bible verse in James Brainerd Taylor's journal and letters, it is easy to see the impact that Essays To Do Good had on the "uncommon" Christian.On June 19, 1820, the then 19-year-old Taylor wrote from Lawrenceville, New Jersey, to one of his sisters:

'To do good and communicate forget not' [Hebrews 13:16] is a maxim which we should keep in continual remembrance. The more we conform our lives to it, the greater will be our resemblance to our blessed Savior as he lived among men [Acts 10:38]. To do good, we must seek opportunities; and then opportunities will frequently find us.

Since reading Cotton Mather's 'Essays To Do Good,' I feel that I have been exceedingly deficient. In looking back to the time when I first made a public profession of religion [September 15, 1816] . . . I am constrained to say, O what a barren fig-tree I have been [Luke 13:6-9]! My leanness! My leanness! But blessed be the Lord, I have a desire to do good now.

*From John Holt Rice and Benjamin Holt Rice, Memoir of James Brainerd Taylor, Second Stereotype Edition [New York: American Tract Society, 1833], 45-46.In my estimation, Galatians 6:10 could really be used to summarize the Second Great Awakening that Taylor participated in. The verse reads:

Therefore, as we have opportunity, let us do good to all, and especially to those who are of the household of faith.

Because of the multitude of domestic and foreign Evangelical Protestant ministries that were established during the early 19th-century spiritual revival, this formative period of American history has been dubbed by some scholars as the Evangelical Empire and the Benevolent Empire. There was a great balance of the integration of faith and good works (Ephesians 2:8-10), with the student-evangelist J. B. Taylor being one of many examples that could be given.

Today's church in Mather and Taylor's native U.S. could learn much from Essays To Do Good. May we be striving uncommon Christians, "zealous for good works" (Titus 2:14) in response to our being justified by faith in Christ.